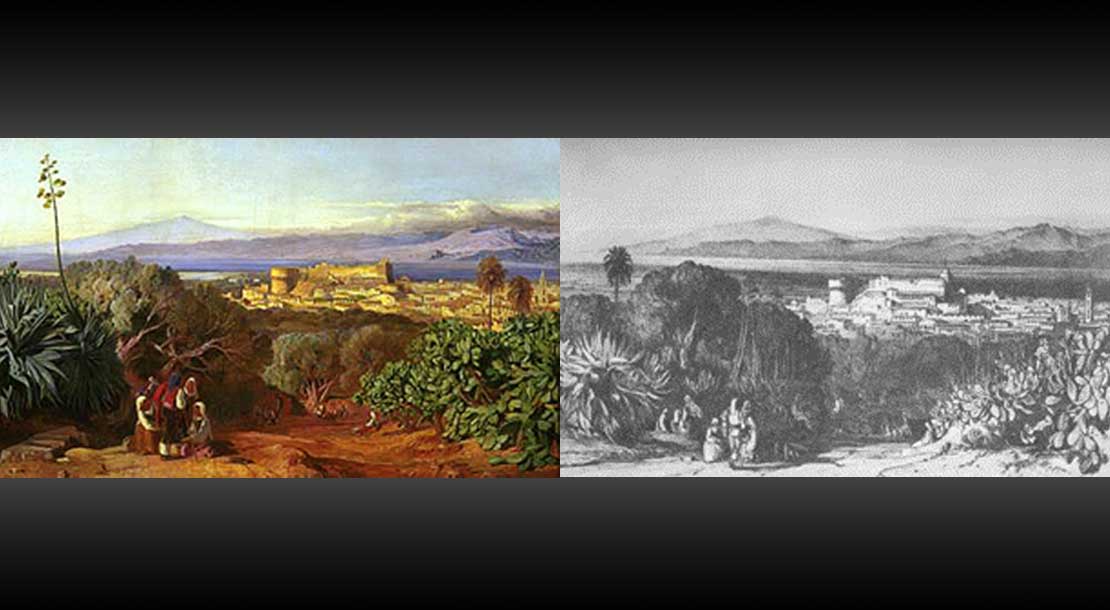

The city of Reggio, point of departure and arrival of Edward Lear's journey, as seen from the slopes of Aspromonte in one of his paintings now exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London (left) and in Lear's original drawing from his Diary published by Rubbettino (right)

Between the topics of medical interest we have covered so far and the revolution of 1848 there is a common ground: the Greek Calabria.

Edward Lear, an English writer and painter, in August 1847 made a journey on foot in Greek Calabria discovering at the end of the voyage that a revolution was breaking out, which became known in Europe as the revolution of 1848.

His "Diary of a journey on foot in Calabria (25 July - 5 September 1847)" documents the first steps of the Italian Risorgimento in Calabria, a historical fact that we Calabrians have been guilty of forgetting …

Few people know that the Italian revolution of 1848 took its first steps in Calabria at the end of 1847.

In order to document these first steps Dr. Daniela Scuncia has prepared a "reading" on the "Diary of a journey on foot in Calabria (July 25 - September 5, 1847)" by Edward Lear.

The book published by Rubbettino (2010) is one of the cornerstones of the diary of travel typical of the nineteenth century. In this case, Greek Calabria is at the center of the narrative of an evocative journey that the English Lear, in the company of his friend Proby and the local guide, Ciccio, started from Reggio Calabria, proceeding to the Ionian coast, and then across the interior to the other sea, the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Lear's diary is particularly interesting because, tinged with typical English humor, it tells of the Calabrian province without too many prejudices and with great enthusiasm.

Returning to the point of departure at the end of August 1847, Lear discovers that a real revolution is underway, which will culminate in the uprisings of Gerace and Reggio in September. This is the beginning of the revolutionary movements that, starting from Palermo (January 12, 1848), will incite all of Italy and then most of Europe.

A video consisting in oral reading of 30 minutes duration by Dr. Daniela Scuncia, accompanied by Salvatore Familiari (guitar) entitled "A walk with Lear: Calabria 1847" will be recorded (the operation has been postponed because of the Covid pandemia) and will be posted in this site.

This reading lends itself well to become the focus of an operation of historical rediscovery of the Italian “Risorgimento” in the territory of Reggio Calabria that will be detailed by Prof. Nino Sammarco, passionate scholar of the Italian Risorgimento in Calabria.

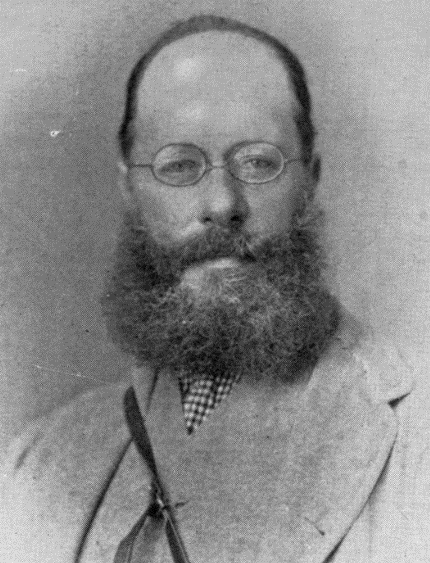

Edward Lear of 1867 that is 20 years after his walking trip in Calabria

In his reading Prof. Sammarco describes the dismay that, at the end of Lear's journey, takes hold of Ciccio, his guide, in contrast to the happiness that transpires from the elation of the waiter who is asked for the keys to the rooms in the inn where the travelers will sleep: "There are no more keys, no more passports, no more Kings, no more laws.

Only love, friendship and freedom, friendship and Constitution" and then, finally: "here are the keys". But the keys are not only the keys of the room, they are the keys that open the truths of his heart of a finally free people.

So begins the adventure of the revolt of Reggio September 2, 1847 involving the city and the District of Gerace which will be followed by the trials, convictions, executions and everything else: in short, "a forty-eight" as it became popularly known and will be explained by Prof. Sammarco in his presentation entitled "The dark clouds of September 1847”.

Further phases of the project

The project will continue with other "readings" that will be transformed into short videos and that will elaborate on the themes of the Italian Risorgimento in Calabria.

There are many narratives of the single exploits of the expedition of the “Mille” (=One thousand) Garibaldini (=followers of Garibaldi who in 1860 sailed from Genova to Sicily in the number of 1000 to start the upraising against the King of Naples ). Some of these can be downloaded for free on the Internet : https://www.liberliber.it/online/autori/autori-m/alberto-mario/la-camicia-rossa/).

There are many narratives of the single exploits of the expedition of the “Mille” (=One thousand) Garibaldini (=followers of Garibaldi who in 1860 sailed from Genova to Sicily in the number of 1000 to start the upraising against the King of Naples ). Some of these can be downloaded for free on the Internet : https://www.liberliber.it/online/autori/autori-m/alberto-mario/la-camicia-rossa/).

One in particular deals with the heroic exploit of 200 “Garibaldini” led by patriot Alberto Mario from Veneto who preceded Garibaldi in August 1860 in the landing in Calabria.

About two thousand insurgents from Greek Calabria joined them on Aspromonte.

The help of the Calabrian insurgents was crucial for the landing of the remaining troops Garibaldi in Melito Porto Salvo and even more for their subsequent advance to Naples where Garibaldi arrived September 7, 1860, cheered by the entire population. It is important to mention that the narrative of Alberto Mario in his "La camicia rossa" (Sonzogno Editore, 1875) is now disputed by those who are convinced that Garibaldi and the Thousand with their enterprise expedition brought to ruin the regions of Southern Italy.

Those who want to form their own independent opinion on that historical period may want to read, amongst others, the stories of two people who really existed, an account of their lives, before and after the expedition of the Thousand.

The first story told by the writer Anna Banti with the title "Noi credevamo" (Oscar Mondadori 2010) concerns Domenico Lopresti, a gentleman from Calabria of unshakeable Republican faith, who spent 12 years in the Borbone prisons until 1860, but remained faithful to his ideals even after.

The second story, narrated by the writer Giuseppe Catozzella with the title "Italiana" (Mondadori 2021) concerns Maria Oliverio, born into a poor Calabrian family, who immediately after the unification of Italy under the name of Ciccilla took the lead of a band of "brigands" and died fighting against the army of the Italian king (former “Piemontese”) which had been entrusted with the task of eradicating with unprecedented ferocity the so-called "phenomenon of Southern brigandage".

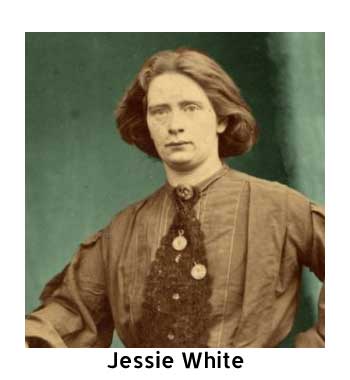

The key to understanding these two stories, only apparently contrasting, can be found in the biography of an  exceptional English woman, Jessie White, the wife of Alberto Mario who participated as a nurse and journalist in the expedition of the Thousand, told by Paolo Ciampi in "Miss Hurricane - The woman who made Italy" (Romano Editore 2013).

exceptional English woman, Jessie White, the wife of Alberto Mario who participated as a nurse and journalist in the expedition of the Thousand, told by Paolo Ciampi in "Miss Hurricane - The woman who made Italy" (Romano Editore 2013).

It is worth quoting here a short excerpt from a review of this biography of Jessie White "....who experienced firsthand the intense period of the Risorgimento from 1859 until the completion of Unification….

Unfortunately, after the death in 1883 of her husband (Alberto Mario), she also witnessed up close and recounted in her books and articles for various journals of the time, the miseries and difficulties of the new united Italy that often turned out to be different and more difficult to build than the projects and hopes (.....).

Thus, at the beginning of the new century, as an old English lady, rich in experience but also in disillusionment, Jessie died in Florence in 1906."

These hints of Jessie's "disillusionment" reflect the feelings of so many of Garibaldi's followers who, like her and her husband Alberto, participated in the venture of the Thousand. Together with Garibaldi at the end of the expedition of the “Thousands” they left Naples on the night of November 7, 1860 after having given the Kingdom of Naples (called at the time of the Two Sicilies) to a dynasty (the Savoia dynasty) that unfortunately never proved to have deserved that gift.

In contrast, Jessie White and Alberto Mario never betrayed their love for the United Italy.

Their social commitment is demonstrated by their writings in later years.

One article in particular, by Jessie, entitled "La miseria in Napoli," is free to download like others from :

https://www.liberliber.it/mediateca/libri/w/white_mario/la_miseria_in_napoli/pdf/la_mis_p.pdf